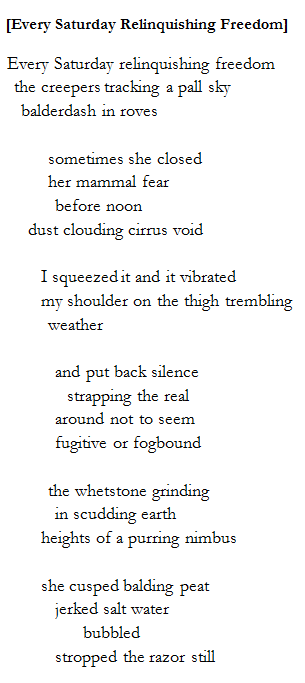

levelheaded: [Every Saturday relinquishing freedom]

Early on, it’s clear there’s a subtle warp to this poem’s syntax. Words are inserted where they may or may not fit. Lines end in the middle of phrases, bucking our train of thought. We could argue the entire poem is grammatically correct, but we would have to argue. The first stanza, for instance, could be a complete grammatical thought, if we accept “balderdash” as a verb. The second stanza could also be its own complete sentence, if we insert some imaginary commas. Point is, the poem creates its own sort of “balderdash.” The poem asks the reader to participate in its creation, and it’s consistent enough to teach us how to read it as we go.

Part of this consistency comes from the poem’s thoroughly enacted tone. In each stanza, it quietly reinforces its preoccupation with grey weather. The the “pall sky,” the “clouding cirrus void,” “trembling weather,” “fogbound,” and the “purring nimbus” paint a static grey landscape, but they also generate suspense. Does this weather portend wickedness? Or more simply, will it rain?

The tone is continued and reinforced by the poem’s antiqued vocabulary. Starting at “balderdash” and running through “whetstone” and “stropped,” the poem blends its vintage speech with the wispy, scientific jargon of cloud identification (“nimbus,” “cirrus”). The dissonance created by these subtly opposing sets of language gives the poem its contemporary quality, but also, where the syntax unsettles the narrative, the language unsettles our ideas of the speaker.

So what’s actually happening? We’re not sure, but in its tightly controlled way, the poem creates an disconcerting sense of danger. By the end, the early “mammal fear” seems like a visceral premonition of something that never fully manifests. The “thigh trembling / weather” introduces a sexual element that seems as out of place as the later “salt water.” And in it’s primary thread, the speaker is anxious about a metaphorical or literal blade. It seems an innocuous blade – meant for shaving, perhaps – but the poem’s final line leaves us hanging. Does the final “still” mean the blade has finally stopped moving? Or does it mean the sharpening – the stropping – of the blade continues still?

– The Editors